What does a registrar do?

Registrars can ofter seem opaque, perhaps even magic. You click a few buttons on your registrar of choice, pay them some money, and eventually there’s a new DNS record pointing to your servers.

But what actually happens behind the scenes to enable that? Before I discuss how your specific domain is handled, let’s discuss the basic organisational structure of DNS. Fair warning here: everything will be a massive generalisation, but feel free to email me if you want more of the sneaky deets (as long as it’s not under NDA).

ICANN

At the top is ICANN, and their division IANA, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers and Internet Assigned Numbers Authority respectively. ICANN is a not for profit organisation. Confusingly enough IANA manages names as well as numbers but oh well!

IANA handles lots of special names and numbers, such as global IP address, autonomous system numbers, media types, and other IP related symbols. Those are a subject for a later time, for now we’re only concerned with their management of the root zone.

The root zone?

DNS is a hierarchical system, and that means at some point there has to be a final point after

which it is not possible to enquire further, this is the root zone. You might think of domain names as being

example.com but they are in-fact example.com., the last . being the root zone (not quite but without an

explanation of the DNS protocol it’ll do for now). The root zone tells everyone who’s responsible for .com,

.uk, .site etc.

Registries

These are the so called top level domains, with every one bar a few of the ~1500 domains delegated to a

commercial registry. For .com, .net and a few others this is Verisign, for .uk this is Nominet,

for .ch and .li this is SWITCH and so on. There is a distinction to be made here between ccTLDs and gTLDS

(country code top level domains, and generic top level domains). For ccTLDs ICANN basically gives registries

free roam on what they do with their zone, whereas for gTLDs there’s a much stricter procedure laid down

by ICANN. Most ccTLDs operate in a similar manner to gTLDs, so I’ll discuss those.

Registrars

Underneath the registry are the registrars. These are companies who maintain a relationship with many registries and with the end user (you!). They’re responsible for customer service and all technical matters that can’t be handled by the registry.

To summarize here’s a graph (with our example registrar ProceedFather):

*-------*

| ICANN |

*-------*

__________/ | \________

/ | \

| | |

*----------* *--------* *---------*

| Verisign | | SWITCH | | Nominet |

*----------* *--------* *---------*

| | | | | |

| \_______|___ \ | |

| ________/ \ \ | |

| / _____________|__|___/ |

| | / | | |

*----* *---------------*

| Us | | ProceedFather |

*----* *---------------*

Why do registrars exist then? To put it simply the registries couldn’t handle the number of clients on their

own. .com has 147 million domains under it, imagine having to handle 147 million clients! Customers also

want a single point of contact for all their domains, without having different accounts for each top level

domain. So that’s where we, and others come in.

What do we do?

You might just think of registrars as middle men out to get more money, and while that can often be true, there’s a lot we have to do in the background to let you buy a domain with a few clicks. Let’s run through the steps that need to happen to let you click “Buy”.

Step one is to establish a relationship with the registry for the TLD. Sometimes this just involves an email, sometimes we have to call, sometimes even by post (remember post?). This will almost always result in them sending over a boring and lengthy contract for us to read over and sign. This details everything we have to do, everything they have to do, and any terms we have to pass on to our customers, aka you.

A redacted version of our agreement with Verisign, boring I know

A redacted version of our agreement with Verisign, boring I know

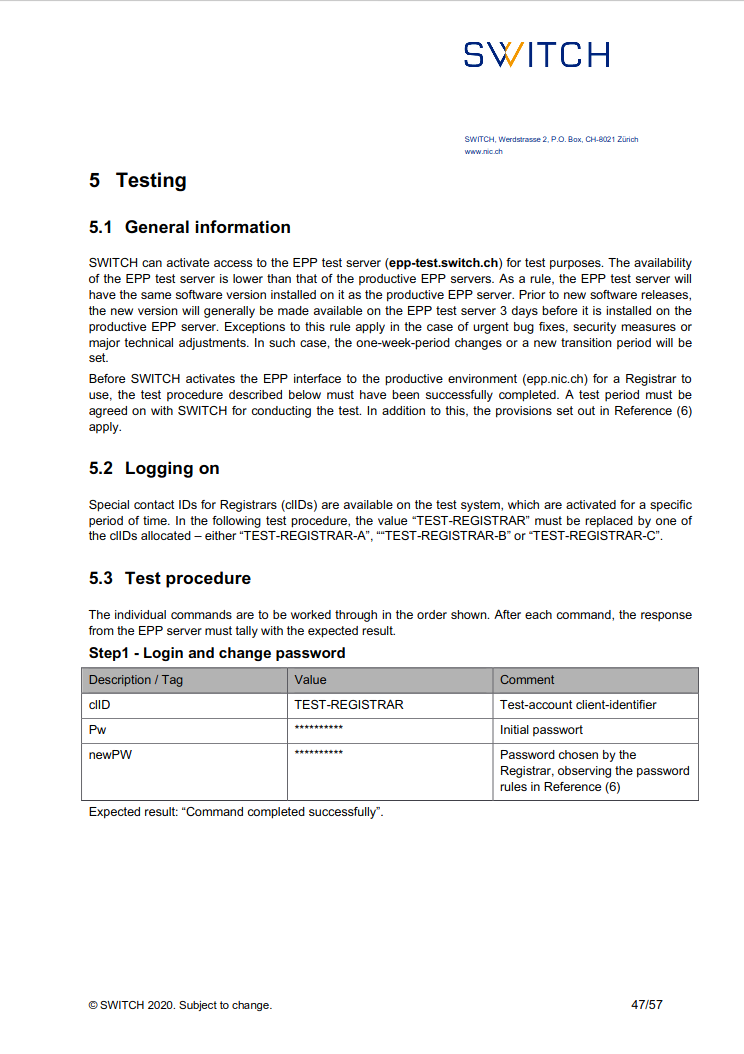

Testing

After we’ve signed that contract, we move onto step 2, proving we’re actually competent at what we do. This usually involves them sending over another big document with a list of things we have to do in a test environment to prove out client can interact with them correctly.

Here’s an extract from the manual for SWITCH, this one’s actually public if you want to read it

here

Here’s an extract from the manual for SWITCH, this one’s actually public if you want to read it

here

These can be quite lengthy and can take up to a full working day to run. I think the record we’ve had so far was 4 hours of submitting commands (manually), along with a few hours of setup and tear down each side. But what are we actually sending them? It’s a protocol called EPP. EPP is standardised in RFC5730. Let’s run through the basics of EPP.

EPP

Currently the only standardised method to transport EPP is over a TLS connection with a 32bit length leader. Here’s an extract from the relevant RFC, no. 5734.

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Total Length |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| EPP XML Instance |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+//-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

EPP is a persistent protocol, that starts with greetings, a login, and then a stream of client messages to which the server streams its responses. EPP as you can see above is an XML protocol, which is not the nicest to deal with.

Let’s run through a few example messages. The first thing a client gets whet it connects is a greeting. This specifies amongst other things; the server you’re connected to, the time according to the server, the versions of the protocol supported, the languages supported, and what services are available on this server.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<epp xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:epp-1.0">

<greeting>

<svID>Example EPP server epp.example.com</svID>

<svDate>2000-06-08T22:00:00.0Z</svDate>

<svcMenu>

<version>1.0</version>

<lang>en</lang>

<lang>fr</lang>

<objURI>urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:obj1</objURI>

<objURI>urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:obj2</objURI>

<objURI>urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:obj3</objURI>

<svcExtension>

<extURI>http://custom/obj1ext-1.0</extURI>

</svcExtension>

</svcMenu>

<dcp>

<access><all/></access>

<statement>

<purpose><admin/><prov/></purpose>

<recipient><ours/><public/></recipient>

<retention><stated/></retention>

</statement>

</dcp>

</greeting>

</epp>

You’ll also notice extensions here. These allow registry operators to add their own things to the session to allow us to ask about non standard things like how much money me have left with them, or to provide the legal type of an entity.

After the greeting we have to login, so things can be billed to the correct account and uh for security. We give our client ID, our password, what version we’re using, what language we like our messages in, and what services we’ll be using.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<epp xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:epp-1.0">

<command>

<login>

<clID>ClientX</clID>

<pw>foo-BAR2</pw>

<options>

<version>1.0</version>

<lang>en</lang>

</options>

<svcs>

<objURI>urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:obj1</objURI>

<objURI>urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:obj2</objURI>

<objURI>urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:obj3</objURI>

<svcExtension>

<extURI>http://custom/obj1ext-1.0</extURI>

</svcExtension>

</svcs>

</login>

<clTRID>ABC-12345</clTRID>

</command>

</epp>

If all is well the server sends back a short response to say “all good, welcome in!”

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<epp xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:epp-1.0">

<response>

<result code="1000">

<msg>Command completed successfully</msg>

</result>

<trID>

<clTRID>ABC-12345</clTRID>

<svTRID>54321-XYZ</svTRID>

</trID>

</response>

</epp>

Something to note in each of these messages in the clTRID and svTRID. These are client and server

transaction identifiers. These help clients keep track of requests when multiple are in flight, and can also

be referenced in the future as part of an audit trail.

After all the formalities are complete we’re free to send our commands to the registry. Let’s look over a simple example, checking if a domain is available.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<epp xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:epp-1.0">

<command>

<check>

<domain:check xmlns:domain="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:domain-1.0">

<domain:name>example1.com</domain:name>

<domain:name>example2.com</domain:name>

<domain:name>example3.com</domain:name>

</domain:check>

</check>

<clTRID>ABC-12345</clTRID>

</command>

</epp>

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<epp xmlns="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:epp-1.0">

<response>

<result code="1000">

<msg>Command completed successfully</msg>

</result>

<resData>

<domain:chkData xmlns:domain="urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:domain-1.0">

<domain:cd>

<domain:name avail="1">example1.com</domain:name>

</domain:cd>

<domain:cd>

<domain:name avail="0">example2.com</domain:name>

<domain:reason>In use</domain:reason>

</domain:cd>

<domain:cd>

<domain:name avail="1">example3.com</domain:name>

</domain:cd>

</domain:chkData>

</resData>

<trID>

<clTRID>ABC-12345</clTRID>

<svTRID>54322-XYZ</svTRID>

</trID>

</response>

</epp>

Here we can see XML namespaces come into use to say we’re sending a check command for the domain

service (urn:ietf:params:xml:ns:domain-1.0). Some other services are hosts and contacts.

This response tells us that example1.com, and example2.com are available to register, whilst example3.com is already registered.

Lots of other commands are available, but I won’t bother detailing them all or we’ll be here all week, go read the RFCs if you’re really interested. There’s a good list of them here.

💸 Money

Now where was I, ah yes, setting up a registry account. Once we’ve completed all the test, and the registry is happy with the results, we’re almost done. Lastly comes the question of money (always problematic isn’t it?). The vast majority of registries operate on a pre-payment scheme, so we have to make sure we’ve got the money with the registry before you submit the order to register and before we’ve got any money from you.

To do this we use the highly advanced linear regression (not really that advanced, but it sounds cool doesn’t it?) to try predict how the money in the registry account will decrease over time and when we need to send another payment to them (which often takes a few days to clear, as they’re mostly international).

After we’ve made our first deposit to the registry we can finally, at long last, start taking registrations for their TLDs!

The end

Thanks for reading this far, I hope you’ve enjoyed, and maybe even learnt something. Feel free to message me (be that Twitter, email, carrier pigeon) if you want to discuss anything further or want some clarifications.